A Return to Bal-Sagoth

Revisiting The Gods of Bal-Sagoth: A Forgotten Gem of Sword-and-Sorcery.

Thirty years. That’s how long it’s been since I last read Robert E. Howard’s The Gods of Bal-Sagoth. I was a teenager back then, devouring pulp fantasy like it was oxygen, and Howard’s tales were my gateway to a world of barbaric heroes, crumbling civilizations, and dark gods. But this particular story? It had faded into the recesses of my memory, overshadowed by the towering presence of Conan and Kull. Recently, I decided to revisit it—and let me tell you, it hit me in ways I wasn’t expecting.

The Story: A Quick Recap

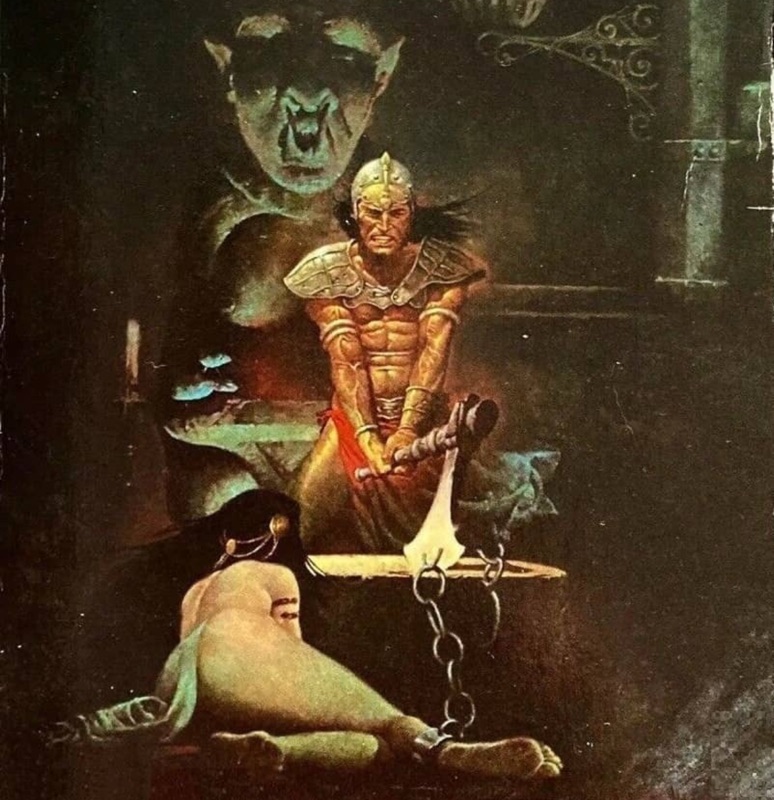

For those unfamiliar, The Gods of Bal-Sagoth is a novella first published in *Weird Tales* in 1931. It follows Turlogh O’Brien, an Irish outlaw, and Athelstane, a Saxon warrior-turned-Viking, as they survive a shipwreck and find themselves on an ancient island ruled by the decadent city-state of Bal-Sagoth. The city is steeped in superstition and ruled by Gothan, a sinister priest who serves the dark god Gol-goroth. Enter Brunhild, a Viking princess who has declared herself a living goddess and is hell-bent on overthrowing Gothan. What follows is a whirlwind of rebellion, betrayal, monstrous forces, and the inevitable collapse of Bal-Sagoth itself.

It’s classic Howard—fast-paced action, larger-than-life characters, and a sense that everything is teetering on the edge of chaos. But reading it now, as an adult with more literary context under my belt, I found myself appreciating layers I missed the first time around.

A Romantic Heart Beneath the Barbarism

What struck me most during this re-read was how much *The Gods of Bal-Sagoth* reflects Howard’s Romantic and Neo-Romantic sensibilities. As a teenager, I saw it as pure adventure—a tale of swords clashing and gods lurking in the shadows. But now? Now I see the deeper currents running through it.

|

| Art by Mr. Zarono on DeviantArt |

Take the setting: Bal-Sagoth is not just another doomed city in Howard’s oeuvre (and there are many). It’s a Romantic symbol—a decaying ruin that represents the fragility of human ambition. Its sapphire towers gleam with faded glory; its rituals are hollow echoes of past grandeur. The city feels alive but dying at the same time, much like Shelley’s 'Ozymandias'. And when it finally crumbles into nothingness at the end, you can’t help but feel that bittersweet pang Howard was so good at evoking—the sense that all human achievements are fleeting.

Then there’s Turlogh O’Brien himself. He’s no Conan—he lacks that larger-than-life presence—but he’s fascinating in his own right. Turlogh is pragmatic and haunted by his past as an outlaw, embodying the kind of brooding individualism that Romantic literature loves to explore. He doesn’t fight for glory or riches; he fights to survive in an indifferent world. His final reflection—“I am King Turlogh of Bal-Sagoth and my kingdom is fading in the morning sky”—is pure Romantic melancholy.

Action Meets Existentialism

Of course, this is still Robert E. Howard we’re talking about, so don’t expect long philosophical digressions or flowery prose. The story moves at breakneck speed—battles erupt out of nowhere; alliances are forged and broken within paragraphs; monsters appear like clockwork to raise the stakes. But beneath all that action lies an existentialist core that feels surprisingly modern.

Howard doesn’t give us neat resolutions or moral victories here. Brunhild’s rebellion succeeds—but only briefly—and her death underscores the futility of her ambitions. The city she sought to rule collapses into ruin before her body is even cold. Even Turlogh and Athelstane’s survival feels less like triumph and more like sheer luck in a chaotic universe.

This sense of impermanence runs through much of Howard’s work, but it feels especially poignant here. Perhaps it’s because Bal-Sagoth itself is such a vivid metaphor for human hubris—a city built on lies and superstition that collapses under its own weight.

Why It Deserved Another Look

So why isn’t The Gods of Bal-Sagoth as celebrated as Howard’s Conan stories? Honestly, I think it comes down to timing and branding. Conan became an icon because he was larger than life—a character who transcended his stories to become a cultural touchstone. Turlogh O’Brien? He’s more grounded, more nuanced—and perhaps less immediately gripping for readers looking for escapism.

But if you’re willing to dig deeper into Howard’s body of work, this novella offers something truly special: a blend of historical adventure and cosmic horror wrapped in a Romantic meditation on power and its inevitable decline. It may not have Conan's swagger or Solomon Kane's unshakable moral compass, but it has heart—and brains—and enough action to keep you glued to the page.

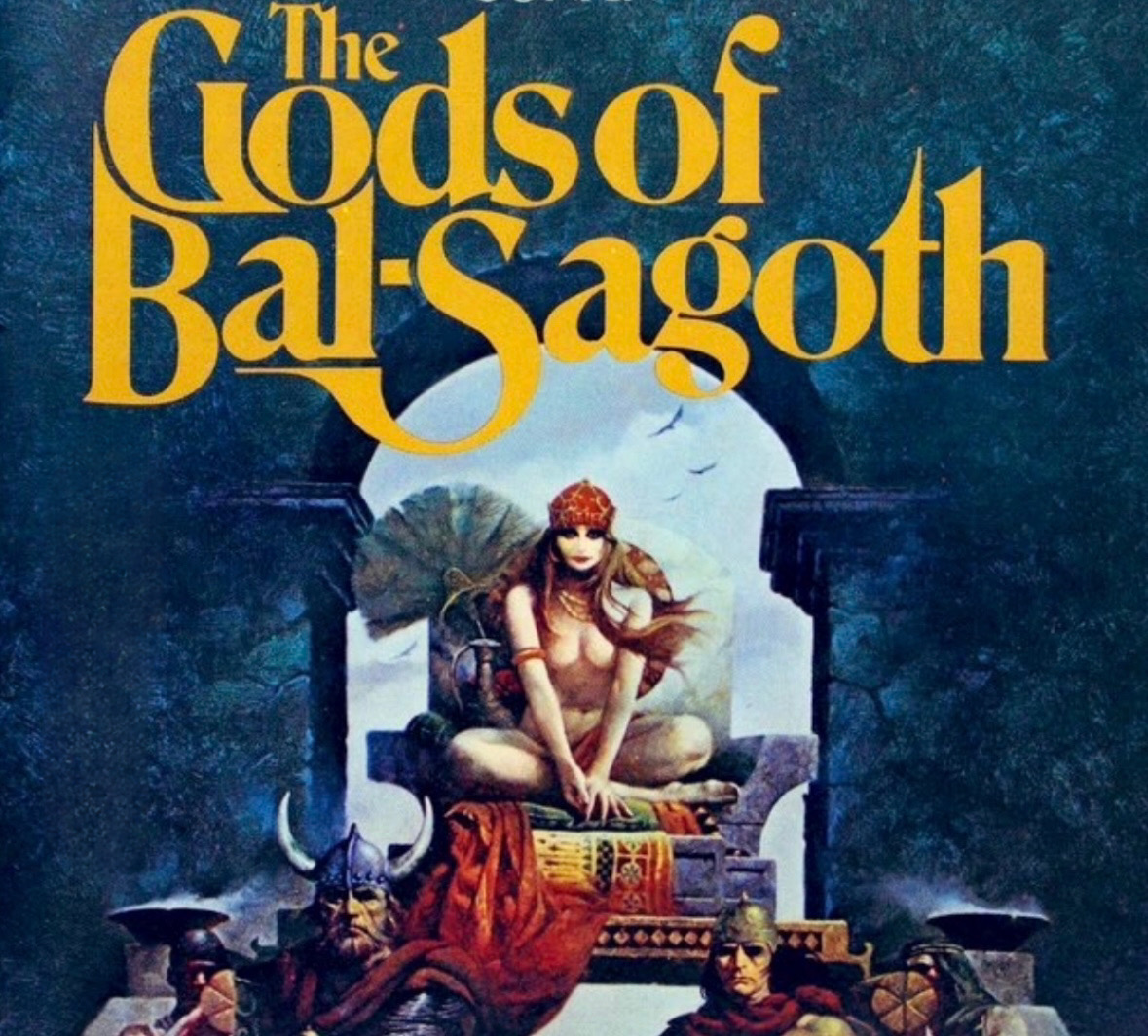

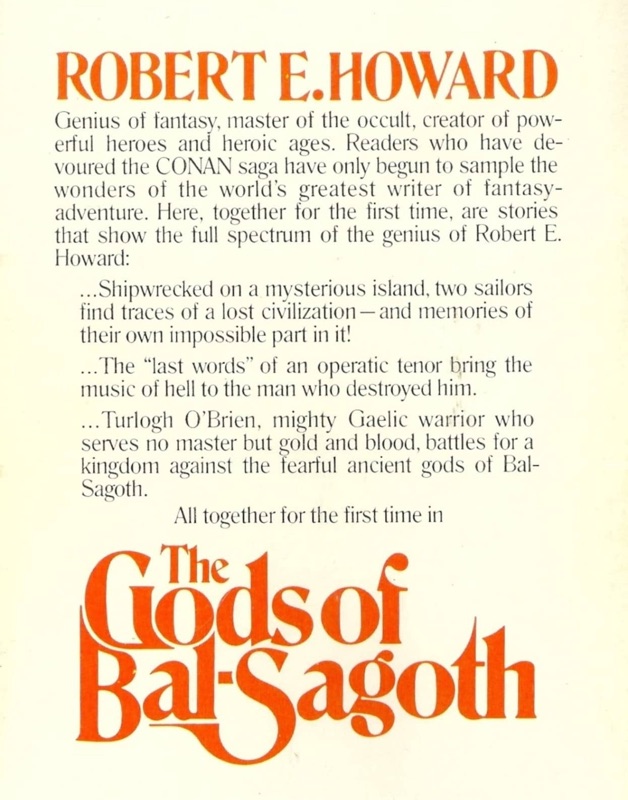

|

| A collection that contains the story |

A Worthy Read

Re-reading 'The Gods of Bal-Sagoth' after twenty years felt like rediscovering an old friend—one who hasn’t aged perfectly but still has plenty to offer if you take the time to listen. It reminded me why I fell in love with Howard's storytelling in the first place: his ability to weave visceral action with deeper themes about humanity's place in an uncaring universe.

If you haven’t read this one—or if it’s been sitting on your shelf gathering dust—I highly recommend giving it another look. It may not be Howard's most famous work, but it’s one that lingers long after you’ve turned the final page. And isn’t that what great storytelling is all about?

Comments

Post a Comment