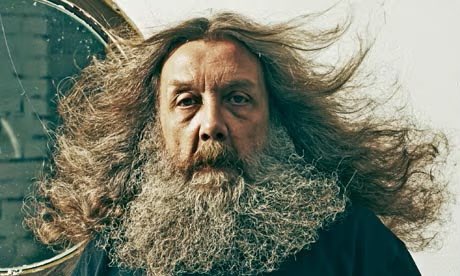

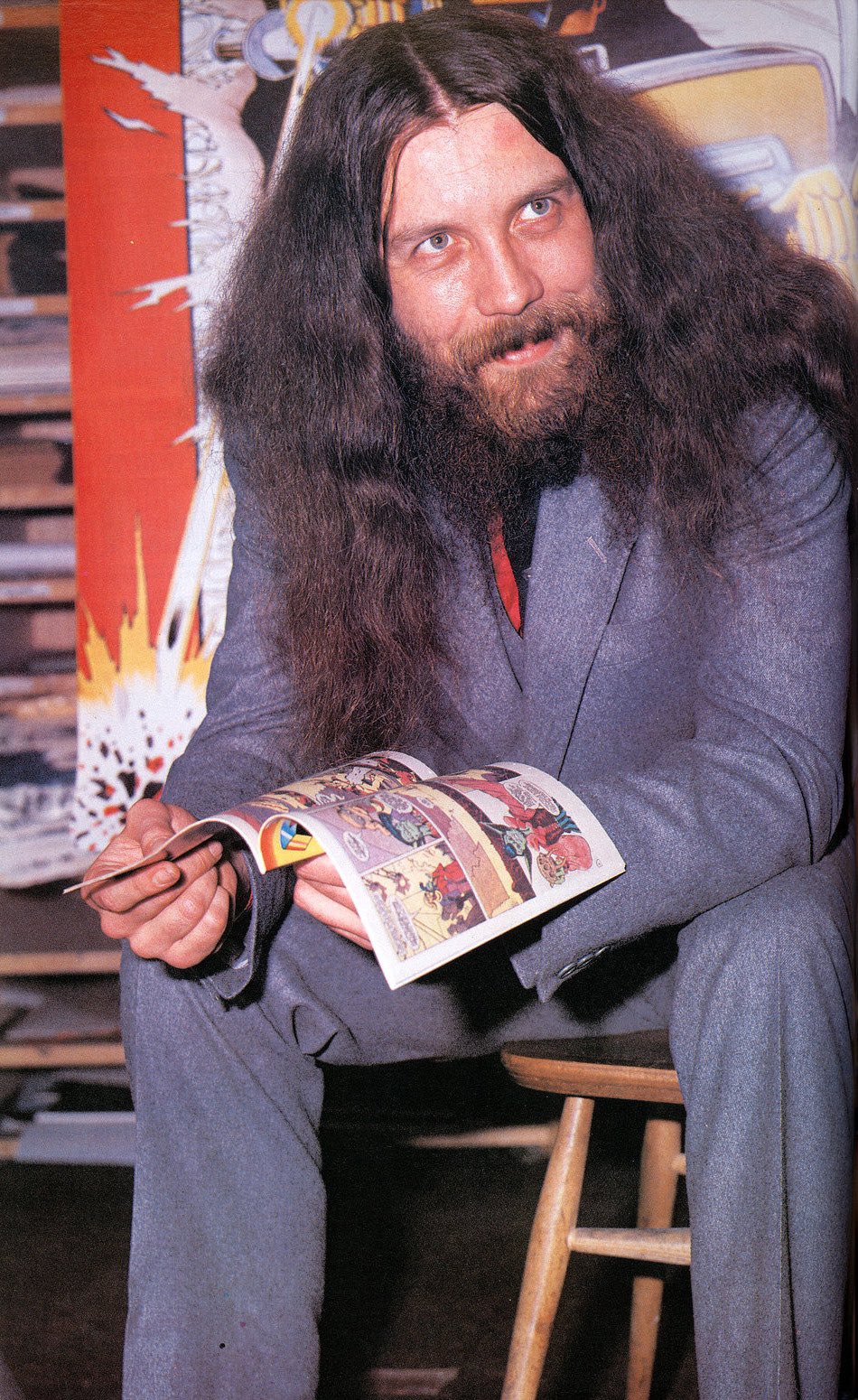

Strange Listicles: The Best Comic Books Written by Alan Moore, Ranked

Alan Moore is a name that resonates with anyone who’s even remotely familiar with the world of comics. The British writer has redefined storytelling in the medium, shaking up the comic book industry and creating works that are not just comic books but literary masterpieces. Today, I’m taking on the monumental task of ranking the 20 best works of Alan Moore. This is no easy feat, given the sheer brilliance of his portfolio, but I’ll do my best to give you a comprehensive guide to his most iconic creations.

So, what do you say, weirdos? Let’s step into the mind of one of the greatest comic book writers of all time.

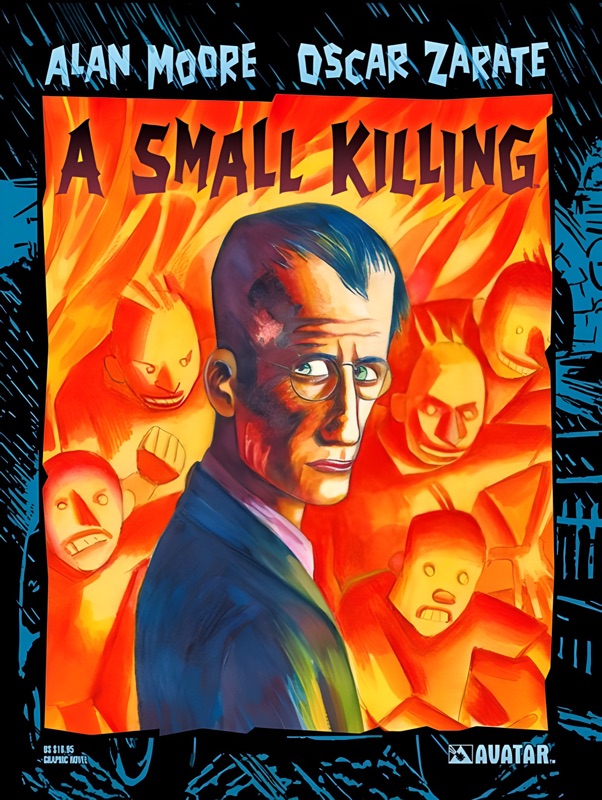

20. A Small Killing (1991)

Synopsis: A Small Killing follows Timothy Hole, a successful advertising executive who begins seeing visions of a strange blue-eyed child following him. As he travels from America back to Britain for an important Cola campaign, these encounters become more frequent and disturbing. The child seems to represent something from Timothy's past—a reminder of the idealistic young man he once was, now haunting him as he compromises his principles for corporate success.

Review: This standalone graphic novel, illustrated by Oscar Zarate, represents one of Moore's most personal and grounded works. Unlike his superhero deconstructions or occult explorations, A Small Killing is a purely psychological thriller that examines the price of success and the ghosts of abandoned ideals.

While the story might feel slow-paced compared to Moore's more action-driven works, it showcases his ability to craft compelling narratives without relying on genre conventions or supernatural elements. A Small Killing might not be as well-known as his superhero work, but it demonstrates Moore's range as a writer and his ability to find profound meaning in ordinary lives.

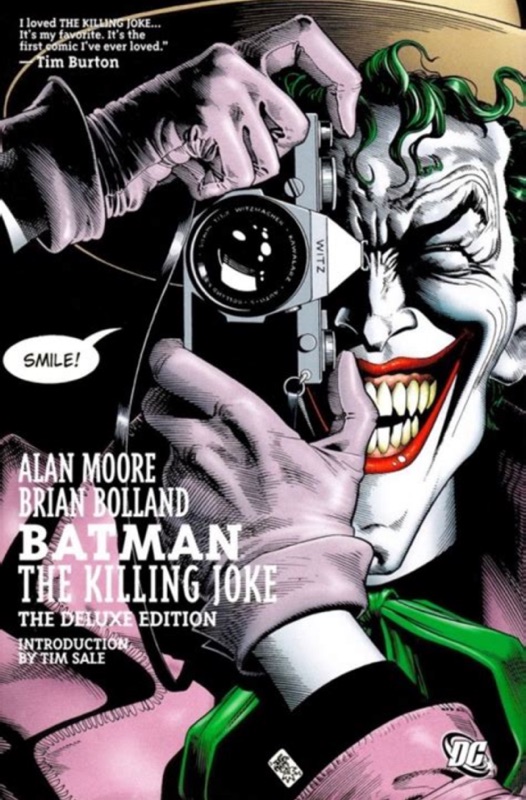

19. The Killing Joke (1988)

Synopsis: The Killing Joke follows the Joker's attempt to prove that anyone can be driven mad by "one bad day," using Commissioner Gordon as his test subject. Through a series of brutal acts—including the shooting and paralysis of Barbara Gordon (Batgirl)—the Joker tries to break Gordon's sanity while Batman races to save his friend. Interwoven with this main narrative are flashbacks to the Joker's possible origin story as a failed comedian turned criminal.

Review: While The Killing Joke is often cited as one of the greatest Batman stories ever told, its position in Moore's bibliography is more complicated. Moore himself has expressed ambivalence about the work, calling it "not very good" and "too violent." Yet the graphic novel, brought to vivid life by Brian Bolland's meticulous artwork, remains a masterclass in psychological horror and character study.

However, the work's treatment of Barbara Gordon as a plot device rather than a character (what would later be termed "fridging") has aged poorly, and Moore's exploration of trauma and madness, while groundbreaking for its time, feels somewhat simplistic compared to his more nuanced work. Despite these issues, The Killing Joke remains a significant piece of comics history, even if it's not Moore at his most sophisticated or thoughtful.

18. Captain Britain (1982-1984)

Synopsis: Moore's run on Captain Britain, created in collaboration with artist Alan Davis, reimagines Brian Braddock's adventures as part of a larger multiverse narrative. The story introduces the concept of the Captain Britain Corps—a multidimensional force of Captain Britains from different realities—and pits our hero against the reality-warping villain Mad Jim Jaspers and the unstoppable Fury, a superhero-killing cybiote that nearly succeeds in destroying Braddock.

Review: While this early work might lack the philosophical depth of Moore's later comics, his Captain Britain run showcases his talent for reinventing existing characters and building complex mythologies. Working with Alan Davis (whose clean, dynamic artwork would help define British comics of the era), Moore transformed what had been a fairly straightforward superhero title into a mind-bending exploration of parallel universes and British identity.

If the series has a weakness, it's that it sometimes feels like Moore is still finding his voice, occasionally falling back on conventional superhero tropes he would later subvert. Nevertheless, his Captain Britain remains an important stepping stone in both his career and the development of British comics in the 1980s.

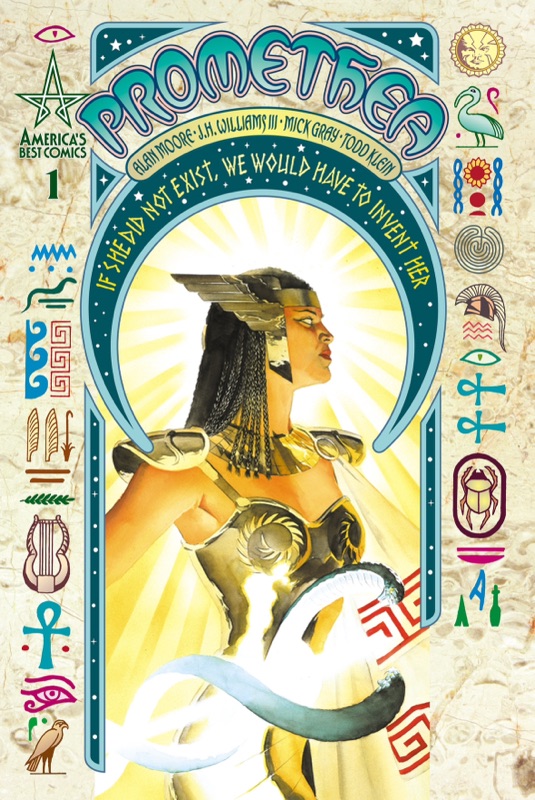

17. Promethea (1999-2005)

Synopsis: Promethea is a deeply philosophical series about a college student, Sophie Bangs, who becomes the new incarnation of Promethea, a mythical warrior who exists across multiple realities. The series explores themes of magic, art, and the nature of reality itself.

Review: This is Moore at his most esoteric. Promethea is a visually stunning journey into the occult, with J.H. Williams III’s artwork complementing Moore’s dense, metaphysical storytelling. It’s not for everyone—some might find it too abstract—but if you’re into deep, thought-provoking narratives, this is a must-read.

16. Supreme (1996-1998)

Synopsis: Moore took over Supreme, a Superman-esque character, and transformed it into a meta-commentary on superhero comics. The series explores the nature of continuity, storytelling, and the evolution of comic book tropes, all while paying homage to the Silver Age of comics.

Review: Moore’s Supreme is a love letter to the history of superhero comics. By deconstructing and reconstructing the archetype of the “perfect hero,” Moore creates a story that’s both nostalgic and forward-thinking. It’s a clever, self-aware take on the genre that shows Moore’s deep understanding of comic book history. Plus, it’s just plain fun.

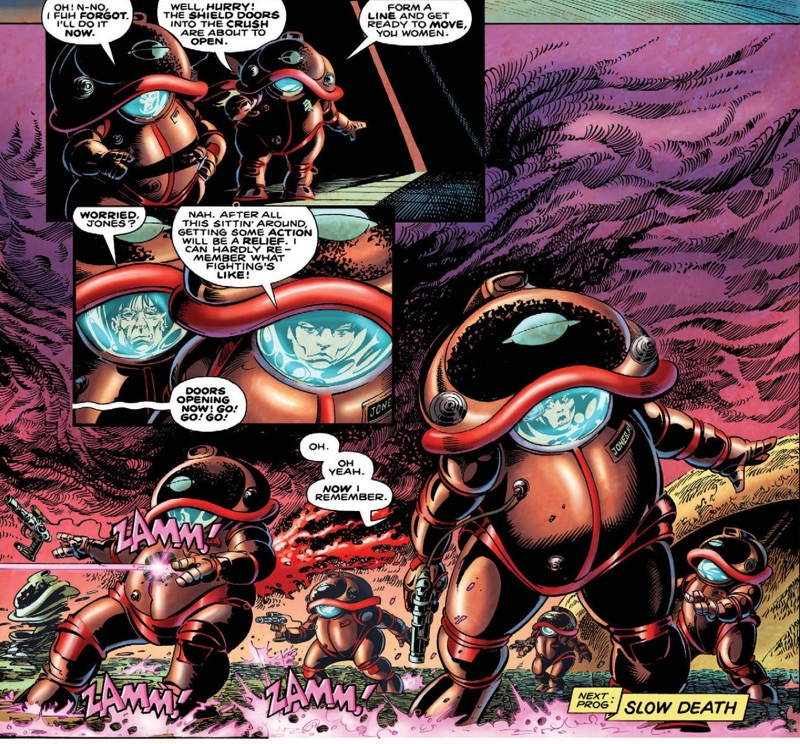

15. D.R. and Quinch (1983-1985)

Synopsis: D.R. and Quinch is a hilariously chaotic series about two alien delinquents—D.R. (short for “Dedicated Revenge”) and Quinch—who wreak havoc across the universe. Their misadventures include everything from crashing a high school prom to starting a nuclear war for laughs.

Review: If you’re in the mood for something completely different from Alan Moore, D.R. and Quinch is your ticket. This is Moore at his most unhinged and comedic, delivering a series of absurd, laugh-out-loud stories that feel like Looney Tunes meets The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy. Alan Davis’s dynamic artwork perfectly matches the anarchic tone of the writing. While it’s lighter than Moore’s usual fare, it’s a testament to his range as a writer. It’s pure, unfiltered fun.

14. The Bojeffries Saga (1983-1992)

Synopsis: The Bojeffries Saga is a sitcom-style comic about the Bojeffries, a bizarre working-class family in Britain. Each member of the family has their own quirks—from a werewolf uncle to a baby with destructive powers—and their everyday lives are anything but ordinary.

Review: This is Moore channeling his inner Monty Python. The Bojeffries Saga is a surreal, darkly funny take on family life, filled with wacky humor and biting social commentary. The series is a collaboration with artist Steve Parkhouse, whose quirky, expressive style brings the eccentric family to life. It’s a lesser-known gem in Moore’s catalog, but it’s a delightful reminder of his ability to blend humor with heart.

13. Providence (2015-2017)

Synopsis: Providence is a Lovecraftian horror series that follows Robert Black, a journalist investigating occult practices in 1919 New England. As he delves deeper into the world of forbidden knowledge, he uncovers a conspiracy that threatens to unravel reality itself. The series is set in the same universe as Moore’s earlier works The Courtyard and Neonomicon.

Review: Providence is Moore’s magnum opus in the realm of cosmic horror. It’s a dense, meticulously researched work that pays homage to H.P. Lovecraft while also critiquing the author’s problematic worldview. The story is layered with symbolism, and Jacen Burrows’ detailed artwork perfectly captures the eerie, otherworldly atmosphere. Providence isn’t just a horror story—it’s a meditation on knowledge, fear, and the fragility of the human mind. It’s a challenging read, but for fans of Lovecraft or Moore’s more esoteric works, it’s an absolute must.

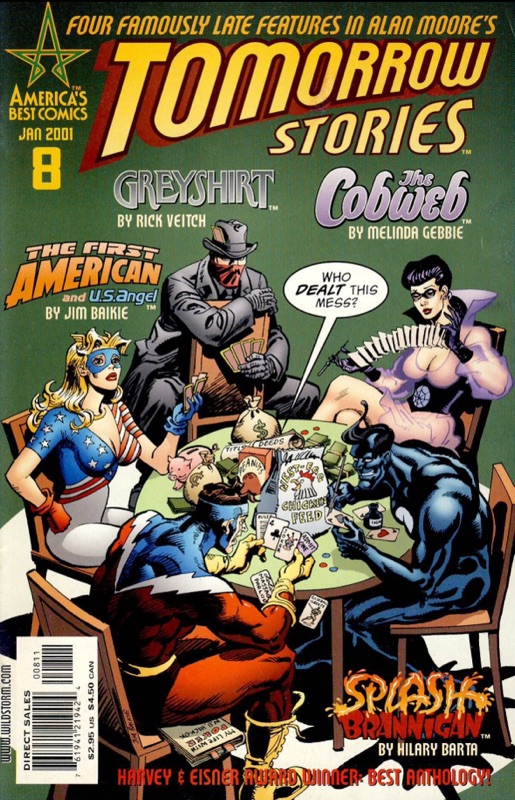

12. Tomorrow Stories (1999-2002)

Synopsis: Tomorrow Stories is an anthology series that showcases Moore’s versatility as a writer. Each issue features a different story, ranging from superhero deconstructions (*Splash Brannigan*) to bizarre comedies (*Jack B. Quick*) and even noir-inspired tales (*The Cobweb*).

Review: If Tomorrow Stories proves anything, it’s that Alan Moore can write just about anything. The series is a playground of ideas, with Moore experimenting across genres and tones. While not every story is a home run, the sheer creativity on display is impressive. It’s a lighter, more playful side of Moore that we don’t often see, and the variety makes it a fun, unpredictable read. Plus, the rotating roster of artists—including Kevin Nowlan, Jim Baikie, and Melinda Gebbie—keeps the visuals fresh and engaging.

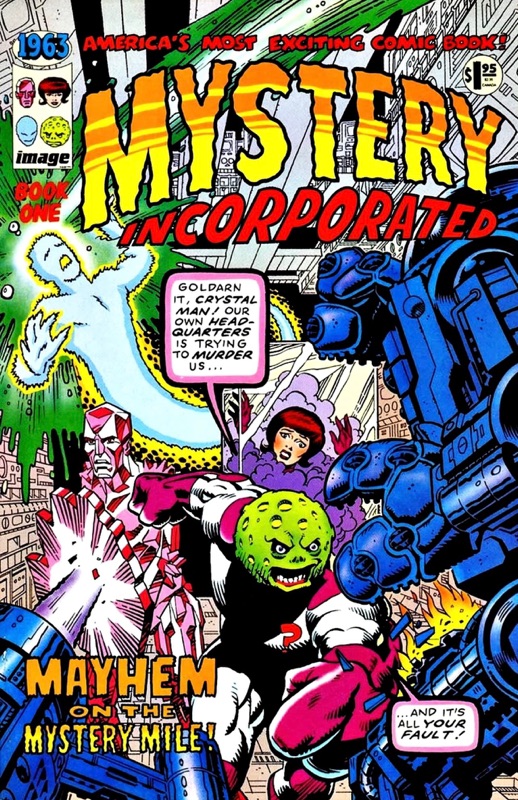

11. 1963 (1993)

Synopsis: 1963 is a six-issue limited series that pays homage to the Silver Age comics of the 1960s. Moore, along with a team of artists, creates a series of standalone stories featuring characters inspired by classic Marvel Comics heroes like the Fantastic Four, Spider-Man, and the Avengers. The series is filled with exaggerated dialogue, bombastic plots, and over-the-top heroics, all wrapped in a meta-commentary on the state of comics in the ‘90s.

Review: 1963 is Alan Moore’s love letter to the Silver Age, and it’s a delightful departure from his usual darker, more complex work. The series is intentionally campy, with Moore and the artists (including Rick Veitch, Steve Bissette, and Dave Gibbons) perfectly capturing the tone and style of ‘60s comics. At the same time, it’s a clever critique of the industry’s shift toward gritty, self-serious storytelling in the ‘90s. While it’s not as deep as some of Moore’s other works, 1963 is a fun, nostalgic romp that shows Moore’s versatility and his deep affection for the medium.

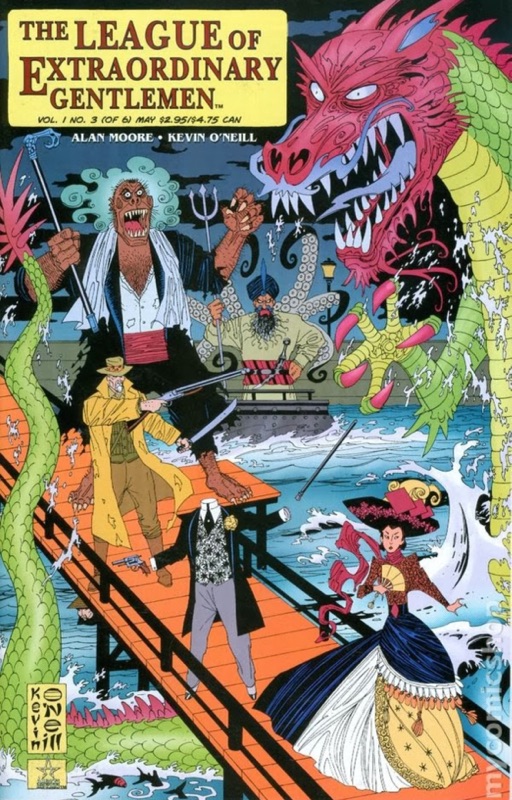

10. The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen (1999-2019)

Synopsis: This series brings together famous literary characters like Allan Quatermain, Captain Nemo, Mina Harker, and Dr. Jekyll/Mr. Hyde to form a Victorian-era superhero team. They face off against various threats, from Fu Manchu to Martian invaders.

Review: The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen is a literary nerd’s dream. Moore’s ability to weave together characters from classic literature into a cohesive, action-packed narrative is nothing short of genius. The series is packed with Easter eggs and references, making it a treasure trove for book lovers. The later volumes get more experimental (and controversial), but the first two volumes are near-perfect.

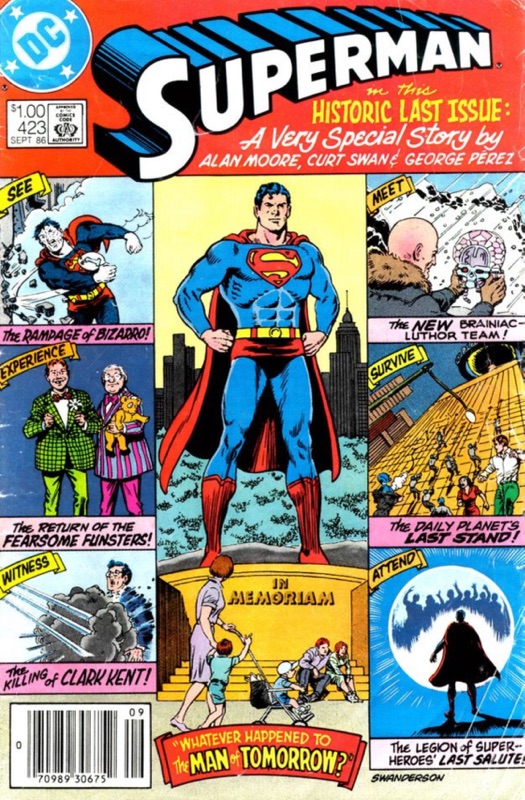

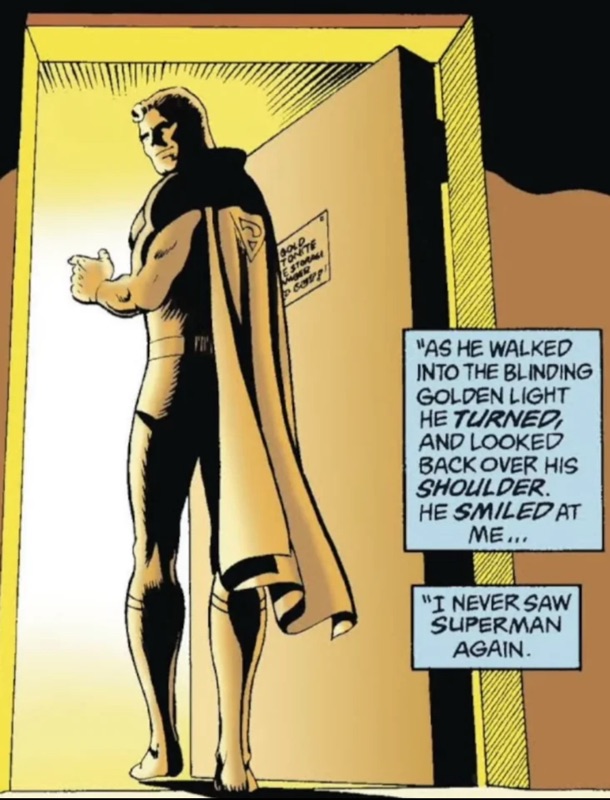

9. "Whatever Happened to the Man of Tomorrow?" (1986) - Superman #423 and Action Comics #583

Synopsis: Written as a "final" Superman story before DC Comics rebooted the character, Whatever Happened to the Man of Tomorrow? imagines a world where Superman faces his ultimate downfall. The story is framed as a reporter interviewing Lois Lane about Superman’s last days, as he confronts his greatest enemies in a climactic battle that forces him to make a heartbreaking decision.

Review: This is Alan Moore’s love letter to the Silver Age Superman, and it’s one of the most emotional Superman stories ever told. Moore captures the essence of the character—his humanity, his sacrifice, and his enduring hope—while wrapping up Superman’s legacy in a way that feels both nostalgic and poignant. Curt Swan’s classic artwork adds to the sense of finality, making this a bittersweet farewell to the Superman of yesteryear. It’s a must-read for any Superman fan, and it remains one of the most iconic Superman stories in history.

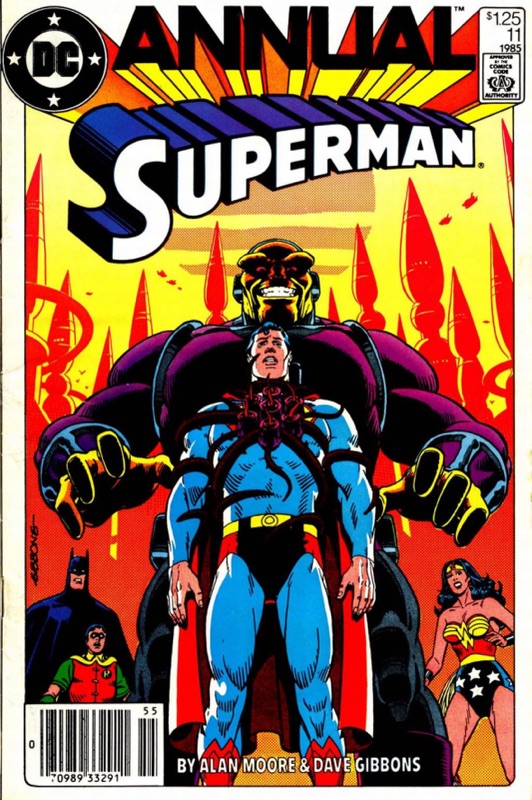

8. "For the Man Who Has Everything" (1985) - Superman Annual #11

Synopsis: In For the Man Who Has Everything, Superman is paralyzed by an alien plant called the Black Mercy, which traps him in a perfect dream world where Krypton never exploded. Meanwhile, Batman, Wonder Woman, and Robin must fight Mongul to free Superman from the illusion.

Review: This is a deceptively simple story with a profound emotional core. Moore explores Superman’s deepest desire—to have his family and home planet back—while also showing the tragedy of living in a fantasy. The story is both a thrilling superhero tale and a meditation on loss, duty, and the cost of heroism. Dave Gibbons’ artwork is clean and expressive, perfectly capturing the emotional weight of the story. It’s a compact, self-contained masterpiece that has been adapted into multiple media, including the Justice League Unlimited animated series.

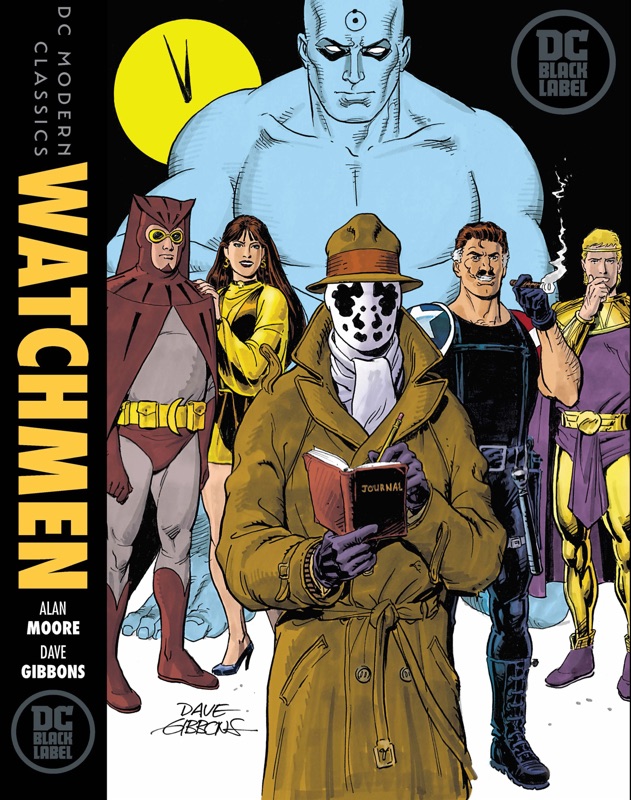

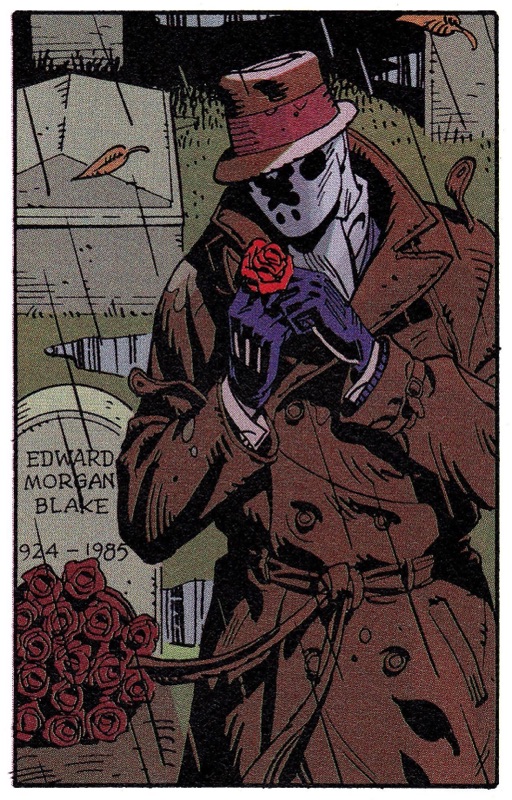

7. Watchmen (1986-1987)

(No, your eyes are not deceiving you - Watchmen is not even in my Top 5. Blasphemy? I think not. It’s a magnificent work, but over the years, it’s become a lot less fun to read, at least for me)

Synopsis: Set in an alternate version of 1985 where superheroes exist, Watchmen follows a group of retired vigilantes as they uncover a conspiracy that could plunge the world into nuclear war. The series explores themes of power, morality, and the nature of heroism, deconstructing the superhero genre in the process.

Review: Watchmen is not just the best work of Alan Moore—it’s arguably the greatest comic book ever written. Moore, along with artist Dave Gibbons, created a complex, multi-layered narrative that redefined what comics could achieve as a medium. The characters—Rorschach, Dr. Manhattan, Ozymandias—are deeply flawed, morally ambiguous, and utterly human, despite their superhuman abilities. The story is packed with symbolism, intricate plot twists, and a groundbreaking use of visual storytelling (that famous nine-panel grid!).

What makes Watchmen so enduring is its ability to examine profound philosophical questions while still delivering a gripping, action-packed story. It’s a critique of the superhero archetype, a meditation on power, and a reflection on the human condition. Everything about Watchmen—from its nonlinear storytelling to its morally ambiguous ending—has left a lasting impact on comics and pop culture. It’s the reason Moore is often called the Shakespeare of comics.

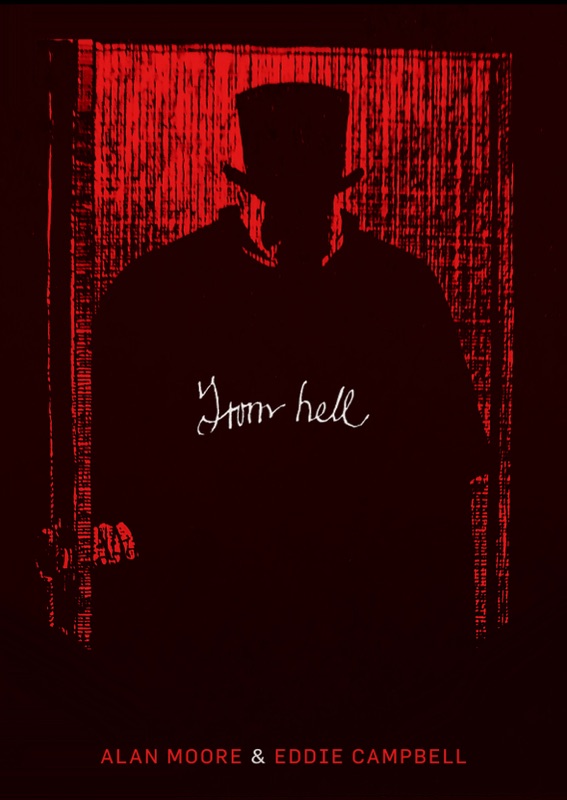

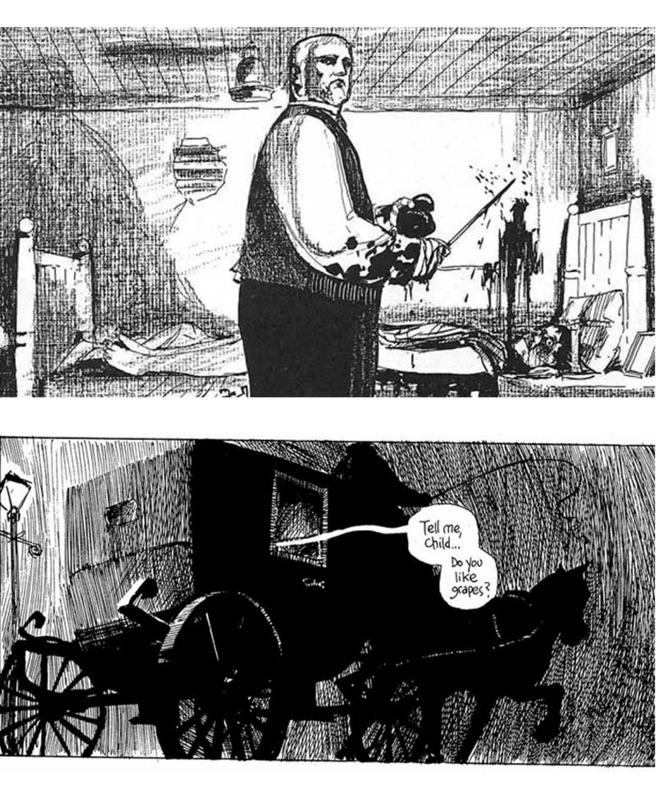

6. From Hell (1989-1998)

Synopsis: From Hell is a meticulously researched graphic novel that delves into the Jack the Ripper murders. Moore weaves a complex narrative that connects the killings to conspiracy theories involving the British monarchy, Freemasonry, and the occult. The story follows Sir William Gull, Queen Victoria's royal physician, as he carries out a conspiracy that encompasses far more than mere murder. Through his eyes, we explore the dark underbelly of Victorian society, where class divisions, misogyny, and mysticism intersect in horrifying ways.

Review: This is Moore at his most ambitious and esoteric. From Hell is a sprawling, dense work that's not for the faint of heart. Eddie Campbell's scratchy, impressionistic black-and-white art perfectly captures the grim, oppressive atmosphere of Victorian London, while his detailed architectural renderings bring the period to vivid life. Moore's writing is meticulous, blending historical fact with speculative fiction to create a gripping, multi-layered narrative that's supported by nearly 50 pages of annotations explaining his research and interpretations.

The work stands out for its unflinching examination of Victorian society's hypocrisies and the way it uses the Ripper murders as a lens to explore larger themes about the birth of the 20th century. It's a harrowing journey into the depths of human evil, and it's widely regarded as one of the greatest graphic novels ever written—not just for its historical accuracy, but for its ambitious scope in connecting one man's madness to the larger madness of an entire era.

And now, dear weirdos, we get to my TOP 5 FAVORITE Moore works. Each entry is slightly longer than what came before, because I have a lot more to say about these titles. Bear with me.

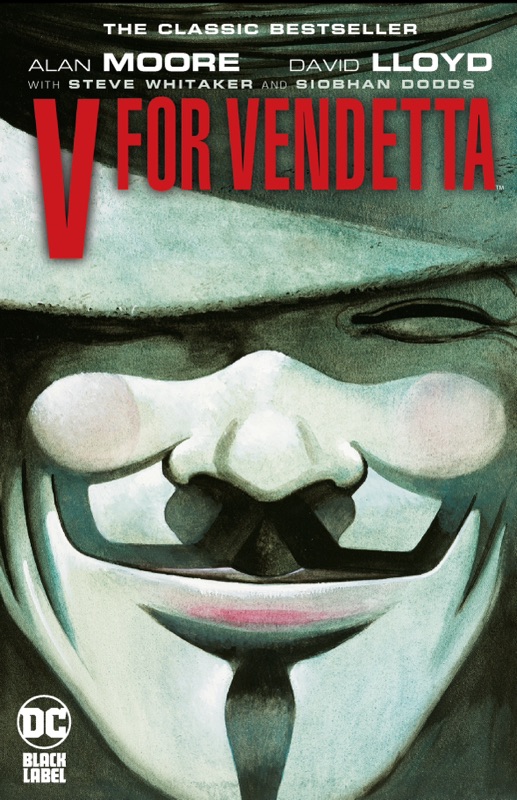

5. V for Vendetta (1982-1989)

Synopsis: Set in a dystopian Britain of the late 1990s (then the near future), V for Vendetta presents a world where a nuclear war has devastated much of the globe, leaving Britain under the control of Norsefire, a fascist regime that maintains power through surveillance, propaganda, and brutal suppression. Into this dark world steps V, a mysterious revolutionary wearing a Guy Fawkes mask, who rescues a young woman named Evey Hammond from the secret police.

The narrative follows V's elaborate plan for revenge against his former captors and his broader mission to destroy the fascist state. Through carefully orchestrated acts of terrorism and manipulation, V systematically dismantles the government's power structures while simultaneously mentoring Evey through a harrowing journey of personal transformation. The story builds toward a climactic confrontation that questions the very nature of justice, revenge, and social change.

Review: V for Vendetta represents Moore at his most politically explicit and philosophically complex. Originally serialized in Warrior magazine before being completed for DC Comics, the series demonstrates Moore's ability to weave multiple narrative threads into a cohesive exploration of power, identity, and social control.

The work is remarkable for several key elements:

- Political Commentary: Moore and Lloyd created the series as a response to Thatcherite Britain, but its examination of fascism's rise through fear, crisis, and manufactured consent remains disturbingly prescient. The story explores how societies surrender freedom for security and how resistance movements can become what they fight against.

- Character Complexity: V himself is a masterfully ambiguous figure—simultaneously hero and terrorist, liberator and manipulator. His relationship with Evey forms the emotional core of the story, raising questions about the moral cost of revolution and the nature of personal freedom.

- Symbolic Depth: The Guy Fawkes imagery, which has transcended the comic to become a real-world symbol of resistance, is just one layer of the story's rich symbolic vocabulary. Moore and Lloyd fill the work with references to literature, music, and theater that add depth to every scene.

Key storylines include:

- "The Land of Do-As-You-Please": V's systematic destruction of government surveillance systems

- "This Vicious Cabaret": A musical interlude that serves as both intermission and thematic summary

- "Valerie": The heart-wrenching story of a letter from a concentration camp victim that becomes a testament to human dignity

David Lloyd's artwork deserves special mention for its innovative techniques:

- The elimination of thought bubbles and sound effects for a more cinematic feel

- The use of muted colors and shadows to create a oppressive atmosphere

- The iconic design of V's mask, which manages to be both emotionally expressive and eerily static

The series explores several interconnected themes:

- The relationship between chaos and order

- The power of symbols and ideas to outlive their creators

- The transformation of personal trauma into political action

- The cycle of violence and whether the ends justify the means

V for Vendetta's influence extends far beyond comics. The Guy Fawkes mask has become a global symbol of protest, used by groups from Anonymous to various political movements. The 2006 film adaptation, while simplified, helped spread the story's core messages to an even wider audience.

What makes V for Vendetta particularly special in Moore's bibliography is its perfect balance of accessibility and complexity. While works like Watchmen might be more intricate in structure, V for Vendetta delivers its philosophical and political messages with remarkable clarity without sacrificing narrative sophistication. It's both a gripping thriller and a profound meditation on the nature of freedom, making it as relevant today as when it was first published.

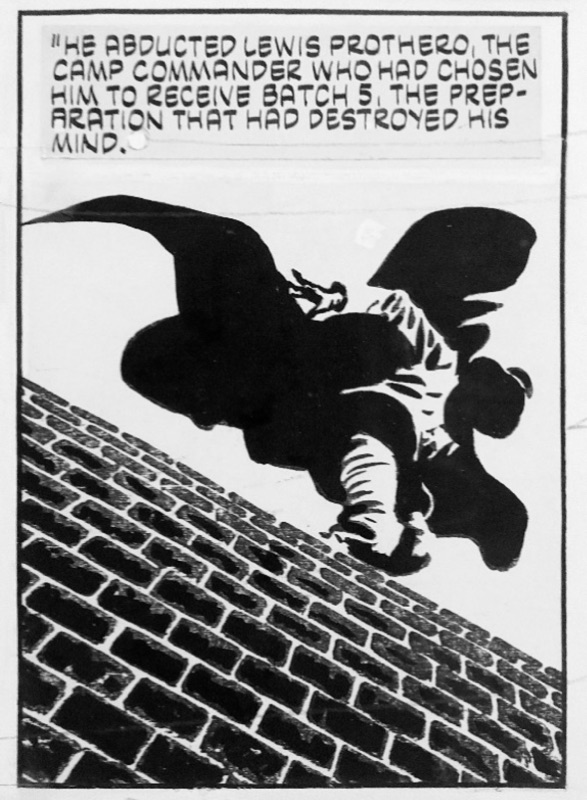

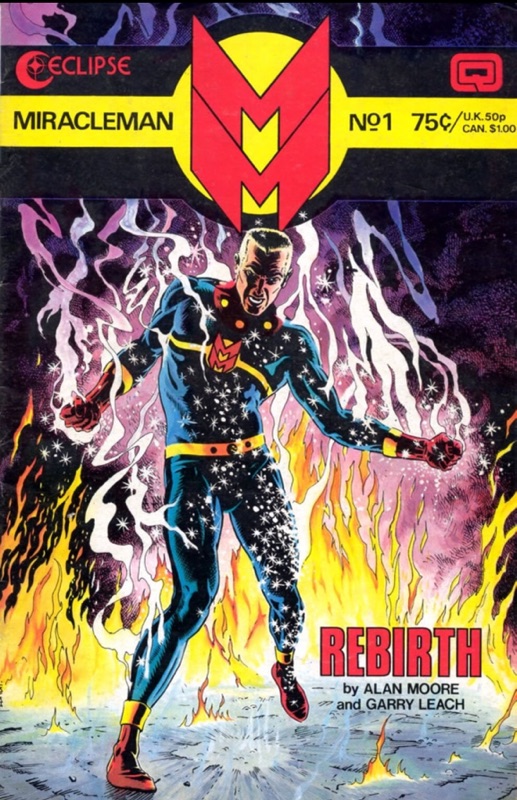

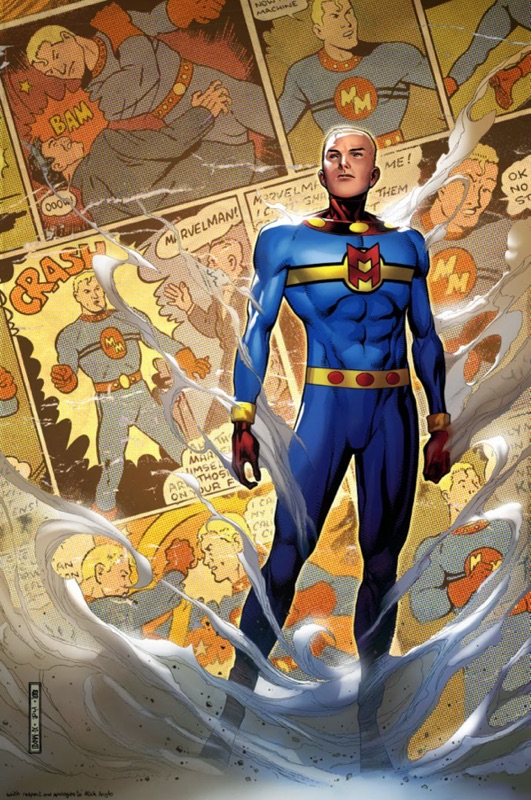

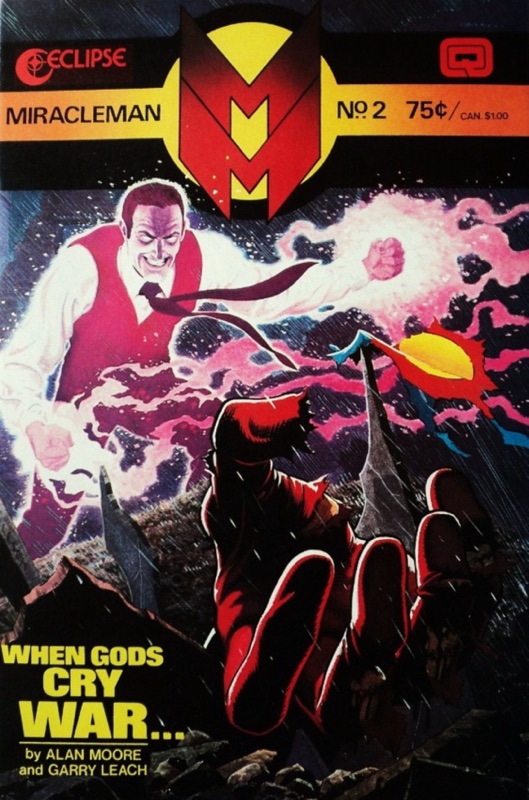

4. Miracleman (1982-1989)

Synopsis: Originally published as Marvelman in the UK's Warrior magazine, Miracleman began as Moore's revival of a 1950s British superhero created as a Captain Marvel clone. The story follows Michael Moran, a middle-aged freelance reporter who discovers that by saying the word "Kimota" ("atomic" backwards), he transforms into the godlike Miracleman. As Moran recovers long-suppressed memories, he uncovers a disturbing truth: his idyllic memories of superhero adventures were fabrications concealing dark government experiments.

The series spans three distinct "books," each darker than the last. Book One explores Moran's rediscovery of his powers and the truth behind his origin. Book Two introduces his sociopathic counterpart Kid Miracleman and culminates in one of comics' most shocking displays of superhuman violence. Book Three examines the global implications of Miracleman's powers as he and his allies reshape Earth into a utopia—though at a devastating cost to human autonomy.

Review: Miracleman stands as perhaps Moore's most unflinching examination of superhuman power and its implications. Working with artists Garry Leach, Alan Davis, and John Totleben, Moore created a series that systematically dismantles superhero conventions while building something far more complex and disturbing in their place.

The series is groundbreaking in several ways:

- Psychological Depth: Moore delves deep into Michael Moran's psyche, exploring the fractured relationship between his human and superhuman identities. The tension between Moran's mundane life and Miracleman's godlike existence creates a fascinating character study.

- Real-World Consequences: Unlike traditional superhero comics, Miracleman shows the genuine horror of superhuman battles. The devastating London sequence in Book Two remains one of comics' most shocking depictions of violence, made more impactful by its logical execution.

- Political Commentary: The series examines how supernatural powers would actually affect geopolitics, economics, and human society. The utopia/dystopia of Book Three raises uncomfortable questions about free will and human agency.

Key storylines include:

- "The Yesterday Gambit": A complex time-travel narrative that foreshadows the series' devastating conclusion

- "The Red King Syndrome": Kid Miracleman's return and the destruction of London

- "Olympus": The transformation of Earth into a posthuman paradise/prison

The series' publication history is almost as complex as its plot. Legal disputes over character ownership led to decades where the series was out of print, adding to its mythical status among comics fans. The artwork evolved dramatically over the run, from Garry Leach's realistic style to John Totleben's baroque fantasyscapes in the final issues.

Miracleman's influence on modern comics cannot be overstated. It established many tropes that would become common in "realistic" superhero stories: government conspiracies, superhuman violence with actual consequences, the logical endpoint of godlike powers. Works like The Boys, Invincible, and Squadron Supreme all owe a debt to Moore's groundbreaking deconstruction.

What makes Miracleman particularly special in Moore's bibliography is how it bridges his earlier, more traditional superhero work with the deeper deconstructions of Watchmen. It's both a celebration and criticism of the superhero genre, maintaining a sense of wonder even as it exposes the genre's underlying problems. While Watchmen might be more polished, Miracleman is arguably more radical in its reimagining of what superhero stories can be.

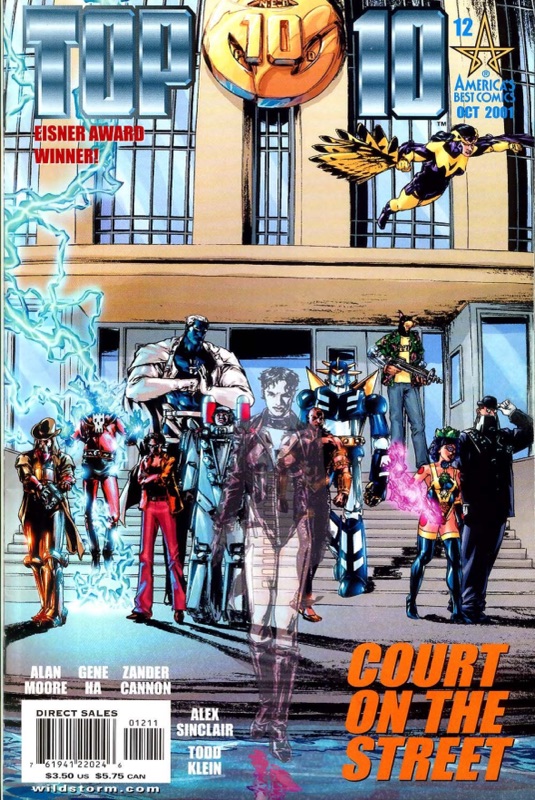

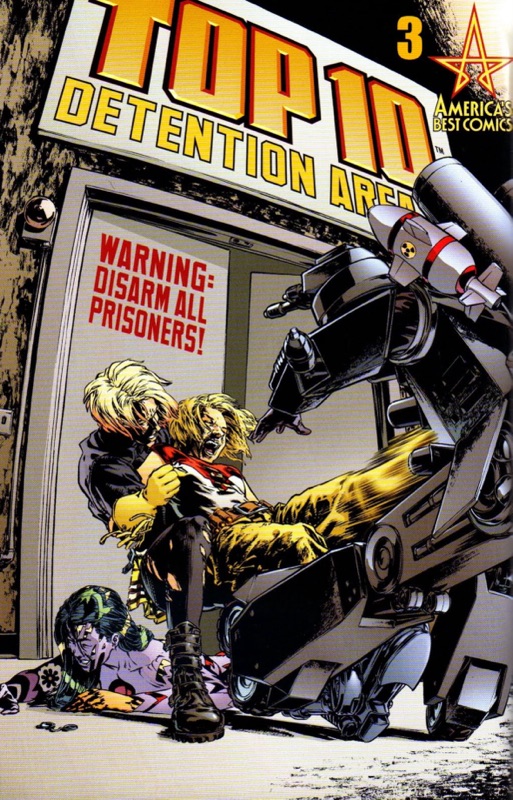

3. Top 10 (2001)

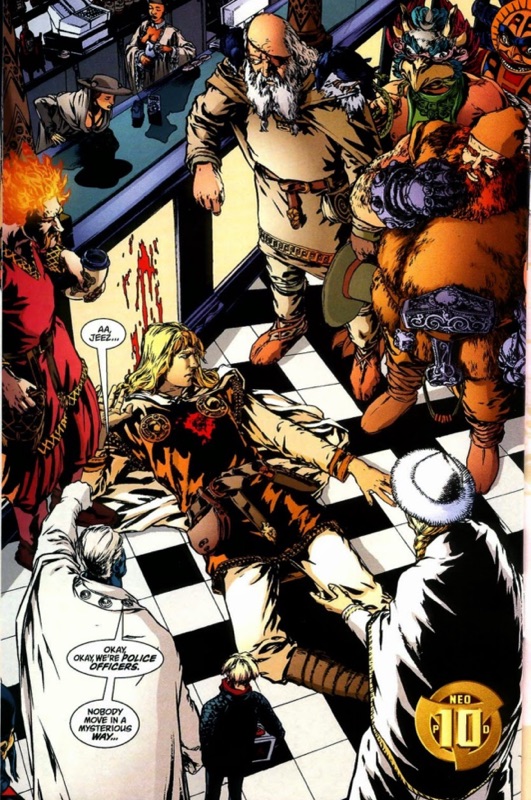

Synopsis: Set in Neopolis (also known as "Science City"), Top 10 follows the daily operations of Precinct 10, a police department in a world where literally everyone—from the beat cops to the hot dog vendors—has superpowers. The story primarily follows rookie officer Robyn "Toybox" Slinger as she joins the force, partnering with veteran cop Jeff Smax. Together with their diverse colleagues, they tackle everything from domestic disputes between telepaths to interdimensional drug trafficking.

Review: Top 10 stands as one of Moore's most inventive and entertaining works, proving he can do "fun" just as masterfully as he does "serious." The series brilliantly combines the gritty procedural elements of Hill Street Blues with the zaniness of silver age comics, creating something wholly unique in the process.

What makes Top 10 special is its attention to detail. Every panel by artists Gene Ha and Zander Cannon is packed with visual jokes, references, and background gags that reward careful readers. You might spot a mouse police officer arresting a cat criminal in one corner, while a group of robotic officers process paperwork in another. This dense world-building creates a living, breathing city that feels both absurd and somehow completely believable.

While not as philosophically dense as Watchmen or as politically charged as V for Vendetta, Top 10 showcases Moore's versatility as a writer. It demonstrates his ability to create compelling entertainment that doesn't sacrifice intelligence or craftsmanship. The series proves that superhero stories can be fun and thoughtful simultaneously, managing to both celebrate and gently satirize the genre conventions it plays with.

In my opinion, Top 10 serves as a perfect entry point into Moore’s bibliography. It's clever without being overwhelming, complex without being confusing, and most importantly, it's just plain fun to read.

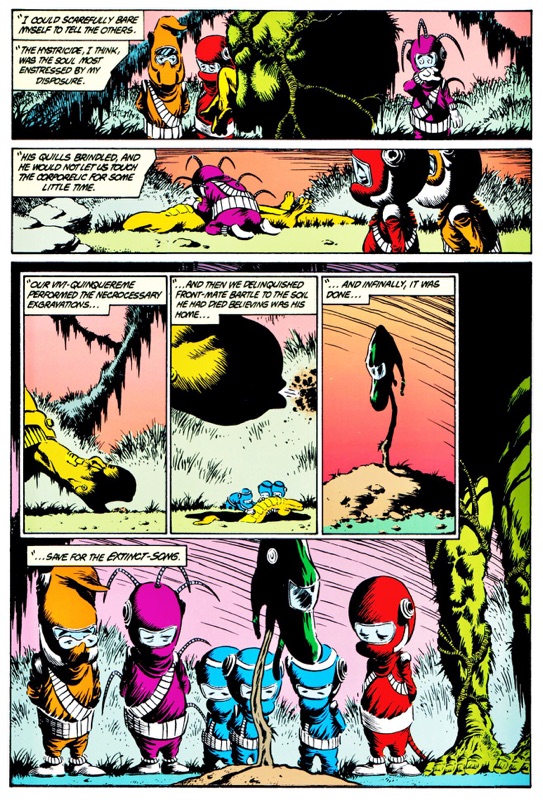

2. The Ballad of Halo Jones (1984-1986)

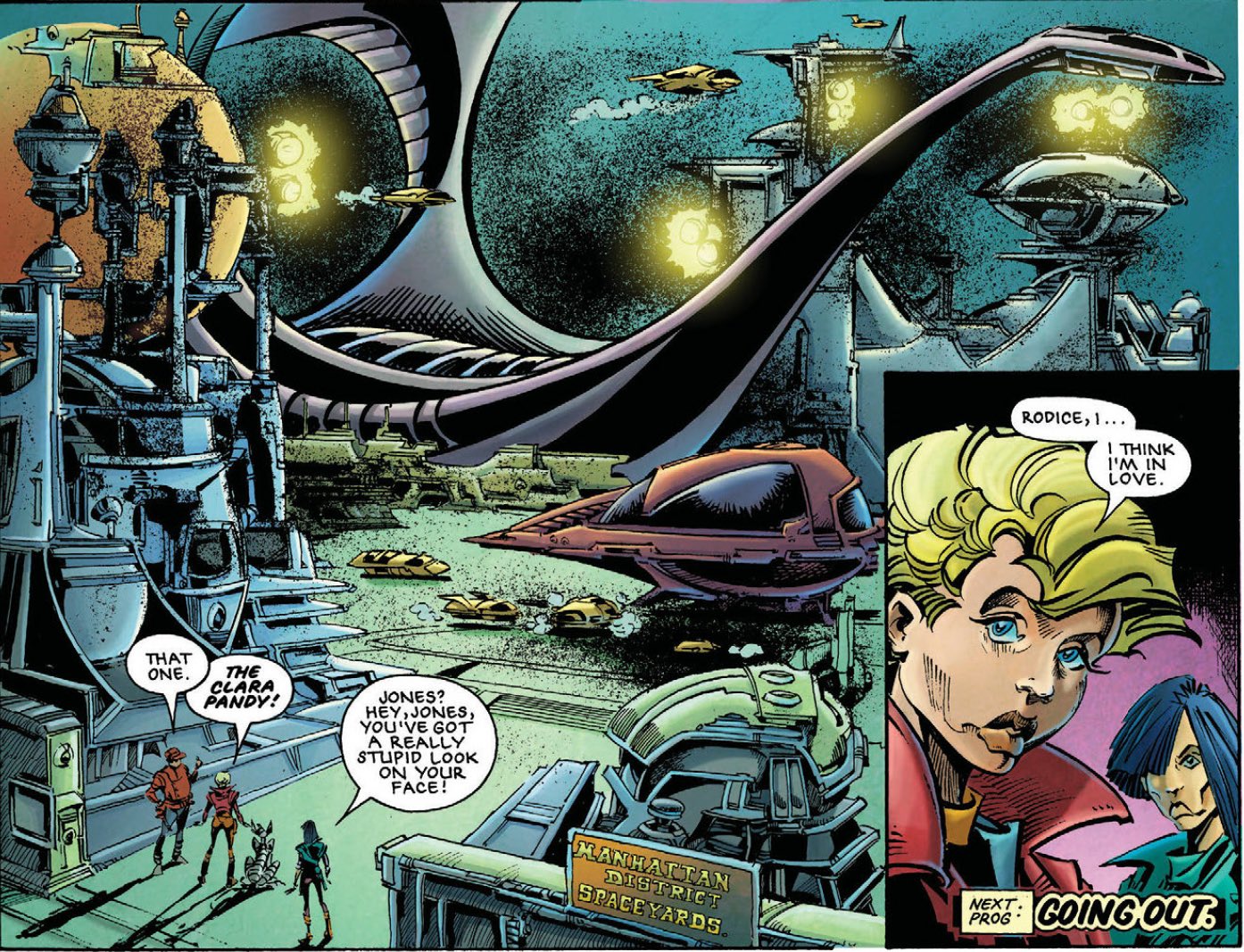

Synopsis: Originally serialized in British comic magazine 2000 AD, The Ballad of Halo Jones follows the extraordinary journey of an ordinary woman in the 50th century. The story unfolds across three distinct "books," each marking a crucial phase in Halo's life. Beginning in the Hoop—a floating housing project off the coast of Manhattan—we watch as Halo evolves from a restless teenager desperate to escape her circumstances into a complex, battle-hardened veteran.

Book One introduces us to Halo's claustrophobic life in the Hoop, where she navigates the daily challenges of surviving in a crowded, violent environment alongside her diverse group of friends, including the robot dog Toby and the mysterious "different basic" Rodice. Book Two follows her adventures as a hostess on a luxury space cruise liner, where she experiences both romance and heartbreak. Book Three takes a darker turn, chronicling Halo's experiences as a soldier in a brutal interstellar war, forcing her to confront the true cost of violence and survival.

Review: The Ballad of Halo Jones stands as one of Moore's most groundbreaking works, particularly in its portrayal of a female protagonist in science fiction. Unlike many of his other series, which deconstruct existing genres or characters, this is a purely original creation that showcases Moore's ability to build complex worlds from scratch.

The series is revolutionary in several ways. First, it presents a female lead who isn't defined by her relationships to men or by conventional heroic attributes. Halo is, as Moore famously described her, "anybody who got out." Her strength lies not in superpowers or exceptional abilities, but in her determination to escape the constraints of her world and forge her own path.

Ian Gibson's artwork deserves special mention for its ability to convey both the grandiose scale of the future world and the intimate emotional moments that define Halo's journey. His detailed backgrounds and expressive character work bring the 50th century to vivid life, from the cramped corridors of the Hoop to the vast emptiness of space.

The series is particularly notable for its sophisticated handling of themes like class struggle, gender politics, and the impact of war on ordinary people. Moore weaves these heavy themes into the narrative without ever becoming preachy or losing sight of the human story at its core. The evolution of Halo's character—from naive teenager to war-weary veteran—is handled with remarkable subtlety and emotional depth.

Tragically, The Ballad of Halo Jones remained unfinished. Moore had planned nine books in total, which would have followed Halo into her eighties, but disputes with 2000 AD over creators' rights led to the series ending after just three books. Despite this, the existing work stands as a testament to Moore's storytelling prowess and his ability to craft compelling, character-driven narratives that transcend genre conventions.

What makes this series particularly special in Moore's bibliography is its accessibility combined with its depth. While works like Watchmen and From Hell can sometimes feel dense or overwhelming, Halo Jones maintains a clear narrative thread while still offering plenty of material for deeper analysis. It's both a gripping adventure story and a thoughtful meditation on free will, social determinism, and the cost of independence.

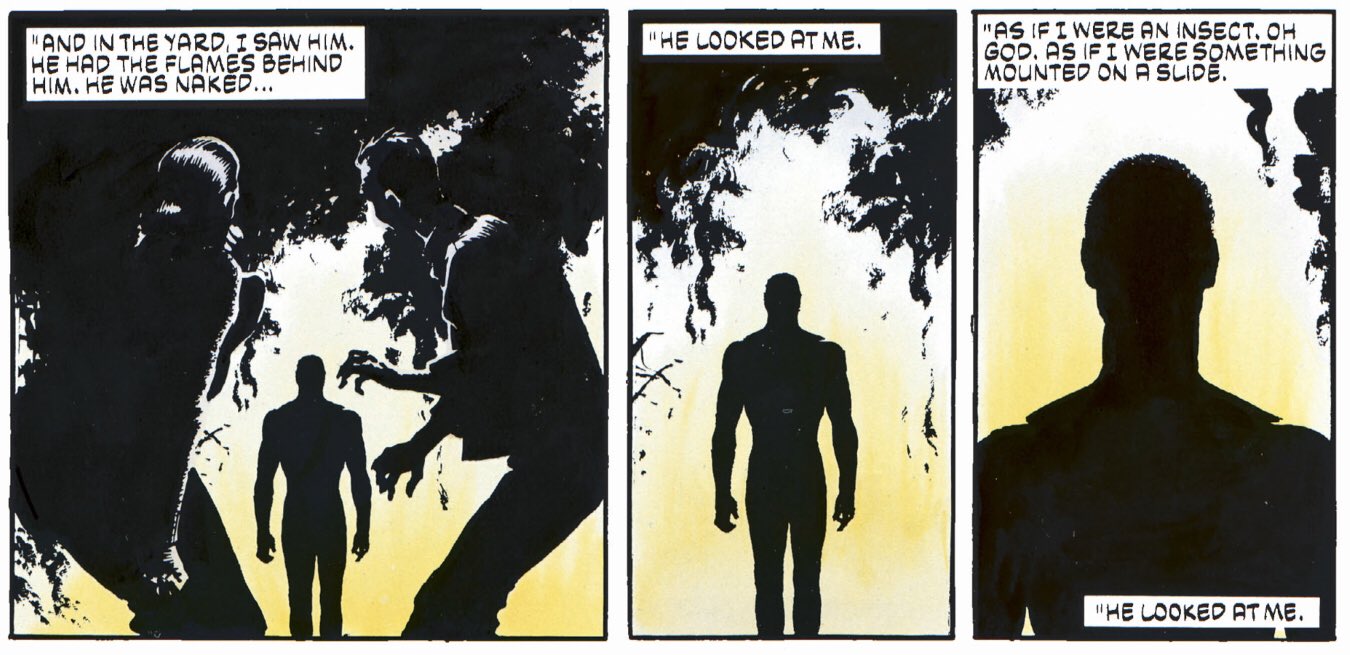

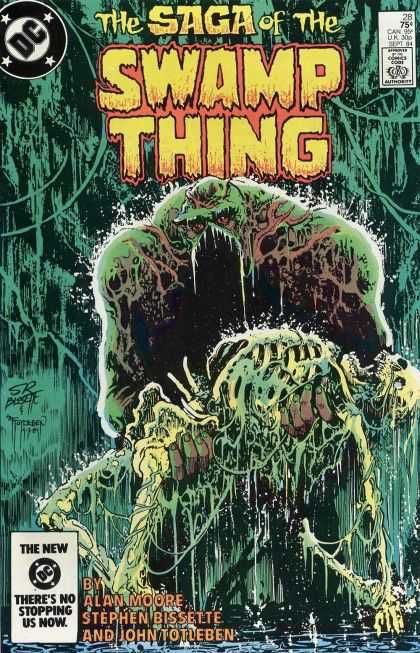

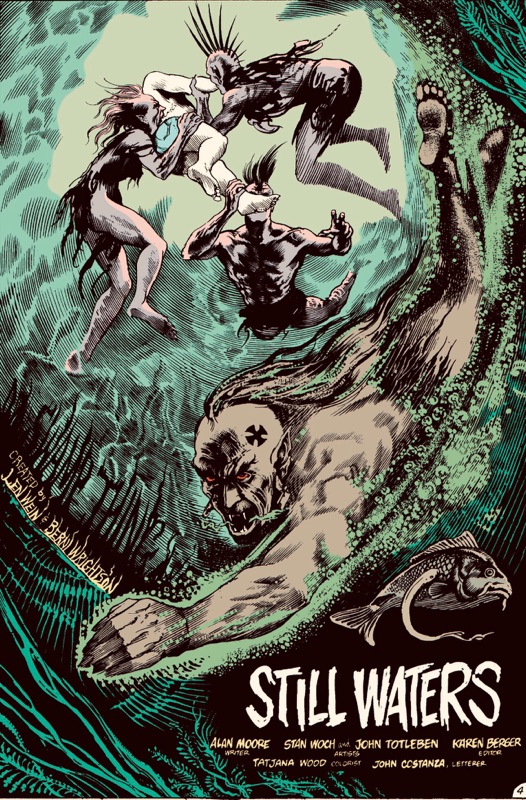

1. Swamp Thing (1984-1987)

Synopsis: When Alan Moore inherited Swamp Thing with issue #20, he immediately revolutionized the character with a stunning revelation: Swamp Thing wasn't Alec Holland transformed into a plant, but rather a plant that thought it was Alec Holland. This philosophical twist set the stage for a groundbreaking run that would redefine horror comics and launch DC's mature readers line.

The series follows Swamp Thing's journey of self-discovery as he embraces his role as the elemental champion of "The Green"—the collective consciousness of all plant life. Along the way, he battles supernatural threats, explores the nature of consciousness, and develops a profound romance with human Abby Arcane. Moore's run introduces several groundbreaking storylines, including the terrifying "The Anatomy Lesson," the psychedelic "Rite of Spring," and the environmentally conscious "The Nukeface Papers."

Review: Moore's Swamp Thing represents a perfect storm of creative innovation. Working with artists Stephen Bissette and John Totleben, whose intricate, shadow-drenched artwork brought a new level of sophistication to horror comics, Moore transformed a standard monster book into a lyrical meditation on nature, consciousness, and humanity's relationship with the environment.

The series is remarkable for several innovations:

- Genre Fusion: Moore seamlessly blended horror, romance, environmentalism, and social commentary. One issue might feature cosmic horror while the next tackled industrial pollution or racism in the American South.

- Artistic Innovation: Bissette and Totleben's artwork broke new ground in comic book storytelling, with elaborate page layouts and detailed, sometimes disturbing imagery that perfectly matched Moore's ambitious scripts.

- Character Development: Moore gave Swamp Thing agency and complexity far beyond his monster-movie origins. His romance with Abby Arcane remains one of comics' most touching and mature relationships.

- World-Building: The series introduced or reinvented numerous characters who would become DC Comics mainstays, most notably John Constantine, who debuted in issue #37. Moore also expanded DC's supernatural universe, establishing concepts like The Green, The Red (animal life), and The Grey (fungal life) that other writers continue to use today.

The series tackled mature themes with unprecedented sophistication. Moore explored environmental destruction, social justice, sexuality, and spirituality while never losing sight of the human (or plant-human) element at the story's core. His run included several landmark issues, such as:

- "The Anatomy Lesson" (issue #21): A masterclass in horror storytelling that completely reimagined the character's origin

- "Rite of Spring" (issue #34): A groundbreaking issue exploring intimacy between Swamp Thing and Abby

- "The Parliament of Trees" (issue #47): A deep dive into the mythology of plant elementals

The influence of Moore's Swamp Thing cannot be overstated. It paved the way for DC's Vertigo imprint and demonstrated that mainstream comics could tackle sophisticated themes while maintaining commercial success. The series' ecological themes feel more relevant than ever, while its exploration of consciousness and identity continues to resonate with modern readers.

This run represents Moore at his most poetic and imaginative, before the darker themes of Watchmen and From Hell took center stage. It's essential reading not just for comic fans, but for anyone interested in seeing how the medium can tackle profound philosophical and social issues while still delivering compelling entertainment.

Honorable Mentions

Before we wrap up, let's acknowledge some other notable works from Moore's vast bibliography that, while not making the top 20, deserve recognition:

Tom Strong (1999-2006): Part of Moore's America's Best Comics line, Tom Strong is a loving homage to pulp heroes and silver age comics. Following the adventures of a science hero raised in a high-gravity chamber on a remote island, the series is more optimistic and playful than much of Moore's work. While it lacks the depth of his more celebrated titles, it showcases his ability to write pure, entertaining adventure stories with heart.

Lost Girls (1991-2006): A controversial collaboration with artist Melinda Gebbie (who would later become Moore's wife), Lost Girls reimagines Alice from Alice in Wonderland, Dorothy from The Wizard of Oz, and Wendy from Peter Pan meeting as adults in a hotel on the eve of World War I. The work, which Moore describes as "pornography," explores sexuality, fantasy, and the relationship between sex and art. While beautifully crafted, its explicit nature and subject matter make it one of Moore's most divisive works.

Neonomicon (2010-2011): A sequel to The Courtyard and prequel to Providence, this Lovecraftian horror story follows two FBI agents investigating cult activity. While it features some of Moore's most disturbing content and clever meta-commentary on Lovecraft's themes, its extreme violence and sexual content make it difficult to recommend except to the most hardened horror fans.

Cinema Purgatorio (2016-2019): This anthology series, featuring a main story by Moore and Kevin O'Neill, deconstructs various film genres through a series of interconnected black-and-white tales. While it contains some brilliant commentary on cinema history and pop culture, its fragmentary nature and limited availability have kept it from reaching the wider audience it deserves.

These works, while perhaps not Moore's greatest achievements, demonstrate his willingness to experiment with different genres, styles, and themes throughout his career. They remind us that even Moore's "lesser" works often contain moments of brilliance that other writers might spend their entire careers trying to achieve.

Wrapping Up

Alan Moore’s body of work is staggering in its depth, complexity, and creativity. From gritty deconstructions of superheroes (Watchmen, Miracleman) to sprawling epics (From Hell, The Ballad of Halo Jones), Moore has consistently pushed the boundaries of what comics can do.

While ranking Moore’s works is always subjective (and frankly, a little unfair, given how consistently brilliant he is), I hope this list has given you a roadmap to dive into his catalog. His ability to blend genres, challenge conventions, and create unforgettable characters is unmatched.

Moore’s influence can be seen in everything from modern comics to blockbuster films, but his work is best experienced firsthand. So, pick up some of these titles, immerse yourself in his weird genius, and see why Alan Moore is considered one of the greatest storytellers of our time.

Thanks for joining me on this journey through Alan Moore’s greatest hits. And let me know your favorite Alan Moore work in the comments—I’d love to hear your thoughts!

Comments

Post a Comment